Back to the Around WWI calendar

At the start of 1918, Germany was in a strong position and expected to win the war but as the year went on and United States troops began arriving in great numbers, it became obvious to the German generals that they could not win and so they told the German government to stop the fighting.

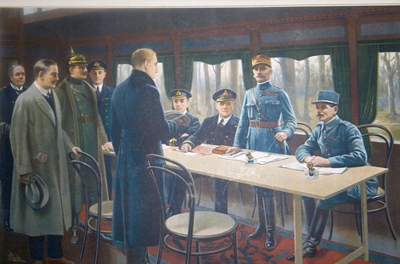

The different sides then started talks to agree to an end to the war. The Germans hoped that any agreement would be based on a 14 point plan Woodrow Wilson, the American President, had drawn up in January 1918. Interestingly, the three men, from Germany, Britain and France who held these talks were not the political leaders. Germany sent a government minister, Mattias Erzberger, who was known to be an opponent of the war, while Britain sent the First Sea Lord, Admiral Wemyss and France sent Marshal Foch who was the supreme commander of all the allied forces.

The different sides then started talks to agree to an end to the war. The Germans hoped that any agreement would be based on a 14 point plan Woodrow Wilson, the American President, had drawn up in January 1918. Interestingly, the three men, from Germany, Britain and France who held these talks were not the political leaders. Germany sent a government minister, Mattias Erzberger, who was known to be an opponent of the war, while Britain sent the First Sea Lord, Admiral Wemyss and France sent Marshal Foch who was the supreme commander of all the allied forces.

They met in a railway carriage which was in a siding in the Forest of Compiègne, a large forest in the region of Picardy, about 37 miles (60 kms) north of Paris. Negotiations began on November 9. The French and British had no intention of using the 14 point plan and were determined that Germany should be made to pay for their actions in the war, both financially and in a way that would mean they could not fight again. When Germany asked for a cease-fire while these negotiations went on, the allies said no.

The terms Marshal Foch laid down said that Germany had to leave the lands in Belgium, Luxembourg and France that they had occupied within 14 days, surrender most of their weapons and all their navy, lose some land that had been German, that the allies would continue the naval blockade of German ports which was causing hunger, misery and death to ordinary German people, and that Germany would have to pay an undisclosed amount to the other countries. Finally, Germany must agree that the war was their fault.

The terms Marshal Foch laid down said that Germany had to leave the lands in Belgium, Luxembourg and France that they had occupied within 14 days, surrender most of their weapons and all their navy, lose some land that had been German, that the allies would continue the naval blockade of German ports which was causing hunger, misery and death to ordinary German people, and that Germany would have to pay an undisclosed amount to the other countries. Finally, Germany must agree that the war was their fault.

Erzberger had a problem because in Berlin the ordinary people had also had enough of the war and were rioting. On the same day the talks began the Kaiser, basically the German King, resigned and there wasn't really any government Erzberger could ask. Besides which it was difficult to get messages out. Eventually he received a message saying he should sign whatever was in front of him and so, at 5.30am on November 11, the armistice, (basically an agreement for peace and no more fighting) was signed and the agreement said all fighting would cease at 11.00am on that day. Incredibly another 2,738 lives were lost before 11.00am.

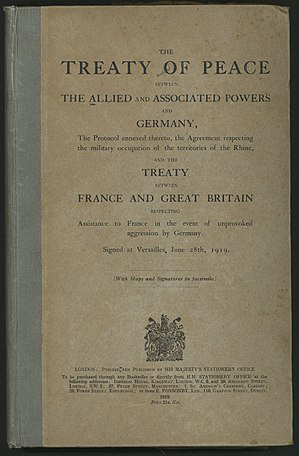

It took 6 months of negotiations until a full peace treaty was signed on 28 June 1919. This was called the Treaty of Versailles, which gives a massive clue as to where it was signed. The Germans still hoped that the treaty might be more of Wilson's 14-point plan but, although the French and British made some concessions, it wasn't.

It took 6 months of negotiations until a full peace treaty was signed on 28 June 1919. This was called the Treaty of Versailles, which gives a massive clue as to where it was signed. The Germans still hoped that the treaty might be more of Wilson's 14-point plan but, although the French and British made some concessions, it wasn't.

Under the terms of the treaty Germany had to accept it was responsible for the war and the allies would confiscate German land, massively reduce the numbers in its army, navy and air-force and demand large amounts of money as compensation, This was known as reparations. Germany had no alternative but to sign. The country wasn't even represented at discussions but the terms caused huge unrest in Germany. Marshal Foch actually thought the treaty was too generous to Germany and declared that "This is not a peace. It is an armistice for twenty years". Twenty years and 65 days later, the Second World War began and many would argue the terms imposed on Germany were, at least partly, responsible for this.

In 1921 Mattias Erzberger was shot dead by members of a gang who felt he betrayed Germany by signing the armistice.

By the way the allies never did get their hands on the German Navy. It had been taken to a place called Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands north of Scotland and, on June 21 1919, the Germans actually sank, or scuttled, their own ships. 52 of the 74 ships there sank.

Back in Britain the end of the war had a great effect too. Initially there were celebrations as soldiers returned home but soon people realised that there were far too many soldiers who were never coming back. Let me give you some figures. If you remember the total population of England was about 30 million and we can assume roughly half were males. The British Army had about three quarters of a million men in 1914. During the war nearly five million were recruited into that army. Most of these men had jobs at home. Someone had to take their place and that is when women began to do the jobs the men had done. During the four years of war nearly a million men in the British army died, mainly killed in action but also some died from wounds and disease. These men were lost forever. On top of that over 2 million soldiers were wounded.

Back in Britain the end of the war had a great effect too. Initially there were celebrations as soldiers returned home but soon people realised that there were far too many soldiers who were never coming back. Let me give you some figures. If you remember the total population of England was about 30 million and we can assume roughly half were males. The British Army had about three quarters of a million men in 1914. During the war nearly five million were recruited into that army. Most of these men had jobs at home. Someone had to take their place and that is when women began to do the jobs the men had done. During the four years of war nearly a million men in the British army died, mainly killed in action but also some died from wounds and disease. These men were lost forever. On top of that over 2 million soldiers were wounded.

All told, amongst all armies, there were 11 million military personnel killed in the war. Add to that 7 million civilians and a total of 23 million people wounded and you can see how devastating this war was. It was initially known as The Great War and called the War to end Wars. It was neither. Great in terms of how many countries became involved, great in the number of lives lost but nothing that kills 18 million members of the human race should ever be called great. As for the war to end all wars, well we already know that 20 years later it all started again.

All told, amongst all armies, there were 11 million military personnel killed in the war. Add to that 7 million civilians and a total of 23 million people wounded and you can see how devastating this war was. It was initially known as The Great War and called the War to end Wars. It was neither. Great in terms of how many countries became involved, great in the number of lives lost but nothing that kills 18 million members of the human race should ever be called great. As for the war to end all wars, well we already know that 20 years later it all started again.

As those who had managed to survive did come back they needed jobs. The government actually told employers to give men the jobs the women had been doing during the war and many women returned to being in service as maids, nannies etc. And children, the lucky ones, could see their fathers again.

In July 1919 Britain was going to hold a Peace Day celebration. An architect called Edwin Lutyens was asked to design a cenotaph for the celebration. A cenotaph is basically an empty tomb or monument in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are somewhere else. The original structure was made of wood and plaster and only supposed to stand for a week. However it was so popular that a new memorial, made out of Portland stone, was installed ready to be unveiled by the King, George V in November 1920.

In July 1919 Britain was going to hold a Peace Day celebration. An architect called Edwin Lutyens was asked to design a cenotaph for the celebration. A cenotaph is basically an empty tomb or monument in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are somewhere else. The original structure was made of wood and plaster and only supposed to stand for a week. However it was so popular that a new memorial, made out of Portland stone, was installed ready to be unveiled by the King, George V in November 1920.

On November 6 1919 King George V had called for all countries in the British Empire to grind to a halt for two minutes of silent reflection, to honour those killed in the First World War. The silence would happen on November 11 at 11.00am, to coincide with the anniversary of the armistice agreement that ended the war. He asked that "All locomotion should cease, so that, in perfect stillness, the thoughts of everyone may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead."

This became the first Remembrance day although, at the time, it was known as Armistice Day.

Many of the soldiers who died in the war were never identified and an idea was put forward to bury one of those unknown soldiers in a tomb in Westminster Abbey. It is said that four bodies were dug up from graves in France or Belgium and the officer in charge of troops in France and Flanders, Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt, chose one body which was then put in a plain coffin. The other bodies were then reburied.

Many of the soldiers who died in the war were never identified and an idea was put forward to bury one of those unknown soldiers in a tomb in Westminster Abbey. It is said that four bodies were dug up from graves in France or Belgium and the officer in charge of troops in France and Flanders, Brigadier General L.J. Wyatt, chose one body which was then put in a plain coffin. The other bodies were then reburied.

On November 11 1920, that coffin containing the unknown soldier was brought through London on a gun carriage, paused at the newly unveiled Centotaph, and then went on to be buried in the west end of the Nave of Westminster Abbey. The grave contains soil from France and is covered by a slab of black Belgian marble from a quarry near Namur with an inscription.

On November 11 1920, that coffin containing the unknown soldier was brought through London on a gun carriage, paused at the newly unveiled Centotaph, and then went on to be buried in the west end of the Nave of Westminster Abbey. The grave contains soil from France and is covered by a slab of black Belgian marble from a quarry near Namur with an inscription.

Since 1920, the Cenotaph has become the focus for the National Service of Remembrance on Remembrance Sunday. Its meaning has developed and the Cenotaph is now a memorial for those who have given their lives in all conflicts since the First World War. The service is attended by Royalty, National and Commonwealth leaders and members of the armed services. The 2 minute silence, first asked for in 1919, is observed both at the Cenoptah and around the country, indeed the commonwealth. Wreaths, usually of poppies (more later), are then laid around the Cenotaph. Following that veterans march past laying their own tributes to those who gave their live in the service of their country.

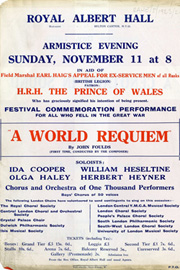

Another annual event of rememberance is held at the Royal Albert Hall in London on the Saturday before Rememberance Sunday. This started back in 1923. The Festival ends with a parade of servicemen and women, alongside representatives from youth uniformed organizations and uniformed public security services of the City of London, down the aisles and onto the floor of the Hall. There is a release of poppy petals from the roof and a two minute silence to commemorate and honour all those who have lost their lives in conflicts. The Festival has been broadcast on BBC radio since 1927, and then also on BBC television.

Another annual event of rememberance is held at the Royal Albert Hall in London on the Saturday before Rememberance Sunday. This started back in 1923. The Festival ends with a parade of servicemen and women, alongside representatives from youth uniformed organizations and uniformed public security services of the City of London, down the aisles and onto the floor of the Hall. There is a release of poppy petals from the roof and a two minute silence to commemorate and honour all those who have lost their lives in conflicts. The Festival has been broadcast on BBC radio since 1927, and then also on BBC television.

In 1927 the concert was simply renamed the ‘Remembrance Festival’ and featured community songs including Pack up Your Troubles, Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty, and Tipperary. The event ended with a service that has now become familiar, featuring The Last Post and ending in God Save the King/Queen.

In 1927 the concert was simply renamed the ‘Remembrance Festival’ and featured community songs including Pack up Your Troubles, Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty, and Tipperary. The event ended with a service that has now become familiar, featuring The Last Post and ending in God Save the King/Queen.

This festival is organised by the Royal British Legion which was set up, without the Royal bit, in 1921. That same year they held a poppy appeal which continues to this day. The original appeal collected money to allow the Legion to care for those who had suffered as a result of service in the Armed Forces during the war, whether through their own service or through that of a husband, father or son. The suffering took many forms: the effect of a war wound on a man's ability to earn a living and support his family, or a war widow's struggle to give her children an education. Their work continues to this day for all servicemen who need help.

Finally, why do we buy poppies and why are they a symbol of our remembering. There are several answers. The scarlet corn poppy grows naturally in conditions of disturbed earth throughout Western Europe. In late 1914, the fields of Northern France and Flanders were once again ripped open as World War One raged through Europe's heart. The poppy was one of the only plants to grow on the otherwise barren battlefields. A Canadian surgeon, John McCrae, wrote a poem called “In Flanders Fields” and the poppy came to represent the tremendous loss of life that had happened there. This is his poem:-

Finally, why do we buy poppies and why are they a symbol of our remembering. There are several answers. The scarlet corn poppy grows naturally in conditions of disturbed earth throughout Western Europe. In late 1914, the fields of Northern France and Flanders were once again ripped open as World War One raged through Europe's heart. The poppy was one of the only plants to grow on the otherwise barren battlefields. A Canadian surgeon, John McCrae, wrote a poem called “In Flanders Fields” and the poppy came to represent the tremendous loss of life that had happened there. This is his poem:-

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The poppy was adopted by The Royal British Legion as the symbol for their Poppy Appeal, in aid of those serving in the British Armed Forces, after its formation in 1921.

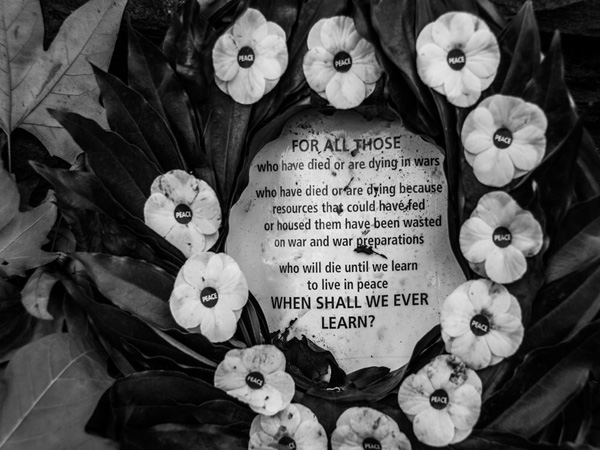

The White Poppy was first introduced by the Women's Co-operative Guild in 1933 and was intended as a lasting symbol for peace and an end to all wars. It was never intended to offend the memory of those who died in the Great War but many veterans felt that its significance undermined their contribution and the lasting meaning of the red poppy. Such was the seriousness of this issue that some women lost their jobs in the 1930s for wearing white poppies.

The White Poppy was first introduced by the Women's Co-operative Guild in 1933 and was intended as a lasting symbol for peace and an end to all wars. It was never intended to offend the memory of those who died in the Great War but many veterans felt that its significance undermined their contribution and the lasting meaning of the red poppy. Such was the seriousness of this issue that some women lost their jobs in the 1930s for wearing white poppies.

Going back to poets and poetry, there are many examples of poems written during and about World War One. You might like to try to find out more.

One verse from one such poem always closes the Festival of Rememberance. It was written by Laurence Binyon. Binyon was too old to serve in the war but wrote his poem, For

the Fallen, when he learned of the suffering in the early years of the war. The verse used is

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Make sure you do.

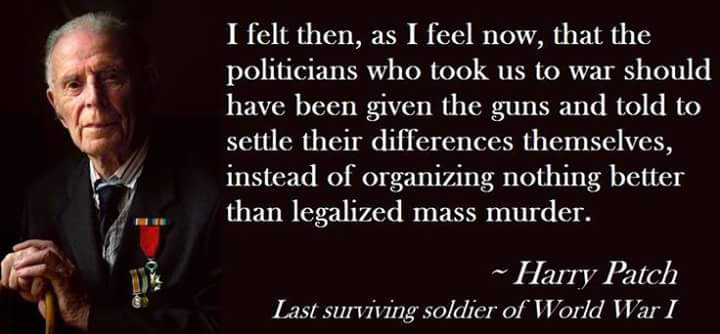

And one last word from Harry Patch who died in 2009 at the age of 111 and was the last surviving British soldier from WWI. I couldn't agree with him more.

Back to 1917AD

Forward to 1919AD