Back to the Around WWII calendar

On January 15 1942 Japanese troops invaded Burma and on September 15 1942, Singapore eventually fell to the might of the Japanese assault resulting in the capture of some 60,000 Allied prisoners against the cost of 2,000 Japanese soldiers. The British prisoners of war were very badly treated. Many of them were forced to work on what became known as the Death Railway.

In October 1942 the Japanese decided to build a bridge across the River Kwai as part of a railway line from Thailand to Burma. The eventual destination was India but, luckily, the Japanese never made it that far. The line was 400 kilometres long and it was finished in August 1943. The aim was to take 3,000 tons of goods and supplies across the continent.

In 2004 I went to Thailand and visited the site of the bridge. In order to construct the railway, and the bridge, the Japanese made use of allied prisoners-of-war; and I use ‘made use of’ deliberately. The prisoners, who were mainly British, Australian and Dutch, were held in prison camps and often had to march kilometres each day to work and then return at night. Their food rations were meagre, their treatment inhuman.

In 2004 I went to Thailand and visited the site of the bridge. In order to construct the railway, and the bridge, the Japanese made use of allied prisoners-of-war; and I use ‘made use of’ deliberately. The prisoners, who were mainly British, Australian and Dutch, were held in prison camps and often had to march kilometres each day to work and then return at night. Their food rations were meagre, their treatment inhuman.

The bridge that now spans the river is not the original. That was bombed in 1944 and subsequently rebuilt. The curved sections were original, the centre sections are new. Part of the original centre section is now in the museum that is close-by. Get in the right position and you can take a picture of the original bridge with the new, still working bridge, in the background. Each day, so we were told, a train runs along this line following the original route.

The museum also has static depictions of the sort of conditions that the prisoners-of-war had to endure. There are many photos as well. It has become a tourist attraction. The bridge itself became famous because of a French novel, written in 1952, and a subsequent film of 1957. The film story was fictional but won universal acclaim and, of course, made the bridge famous although I think I am right in saying the film was made somewhere else in Asia, so my notes say but sadly not where. I had a personal interest as a brother of one of my uncle’s was captured and worked on this railway.

The museum also has static depictions of the sort of conditions that the prisoners-of-war had to endure. There are many photos as well. It has become a tourist attraction. The bridge itself became famous because of a French novel, written in 1952, and a subsequent film of 1957. The film story was fictional but won universal acclaim and, of course, made the bridge famous although I think I am right in saying the film was made somewhere else in Asia, so my notes say but sadly not where. I had a personal interest as a brother of one of my uncle’s was captured and worked on this railway.

Nearby, at Kanchanaburi cemetery, there are the graves of nearly 7,000 men who died in the construction of the railway, and now you see why it was called the Death Railway. It is something like this that, for me, always answers the question, what point is history. I defy anyone, with an ounce of compassion for their fellow humans, not to be moved by this and not to see the futility of war. It solves nothing, it destroys everything. There are no winners. We need, as humans, to see what has been done before to understand we must never allow it again. I believe that knowledge of our past, our mistakes, our successes, is essential for our future. In the same way that I don’t think the car designers of today would be where they are without knowing, or at least using the knowledge of, what Mr Benz and Mr Daimler did all those years ago, the same applies to life. I am not saying that politicians won’t make the same mistakes over and over again, either through greed or stupidity, but if we, the ordinary man and woman, have these reminders, then maybe we might, might, if democracy really does exist, vote out these idiots. In all, it is reckoned that 120,000 people died in the making of the railway and we view that as horrific. Apart from prisoners of war, the rest were civilians from Thailand, Hong Kong and Burma.

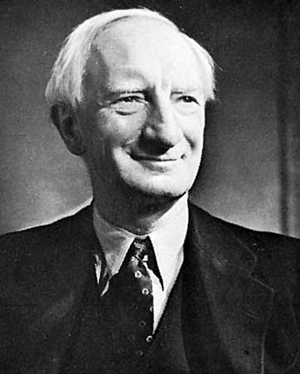

Despite the fact that the country was in the middle of the most serious war it had ever fought, life in Parliament had to go on. In November 1942 a report was presented to Parliament that would have a far reaching effect on the lives of the people of the United Kingdom, including you. The report was made by a man called William Beveridge who was an economist and member of the Liberal Party.

Despite the fact that the country was in the middle of the most serious war it had ever fought, life in Parliament had to go on. In November 1942 a report was presented to Parliament that would have a far reaching effect on the lives of the people of the United Kingdom, including you. The report was made by a man called William Beveridge who was an economist and member of the Liberal Party.

The report set out to remove poverty and want from Britain. Beveridge believed there were 5 great evils in society; Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness. The report suggested a system of social security which would be run by government. Beveridge believed that although he could not see his ideas being put into practice until after the war, this was an opportunity to put things right.

He wanted to see a system where all working age people made a national insurance contribution to the government and, in return, they would have benefits when they were unemployed, sick, retired or widowed. He argued that this would provide a minimum standard of living for all. At the time, and partly because of deaths in the war, the population of Britain was falling and Beveridge wanted particularly to make sure there were safeguards for children and young mothers.

Beveridge wanted to see full employment. Funnily enough, when economists and government minsters talk of full employment they usually mean unemployment of less than 3% of the workforce. They don't mean everyone has a job. He believed that if healthcare and pension costs were moved to the government, firms would have more money to employ people and that healthier workers would also produce more goods.

Forward to 1943AD